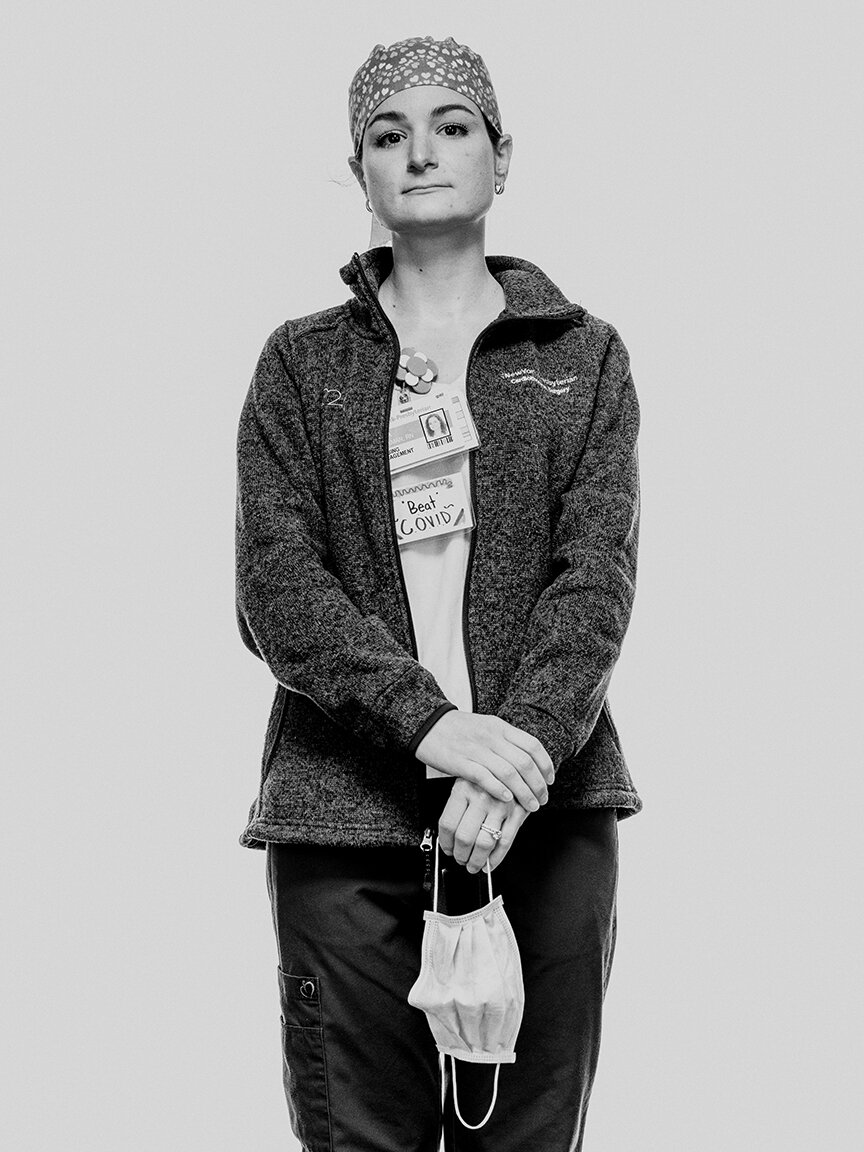

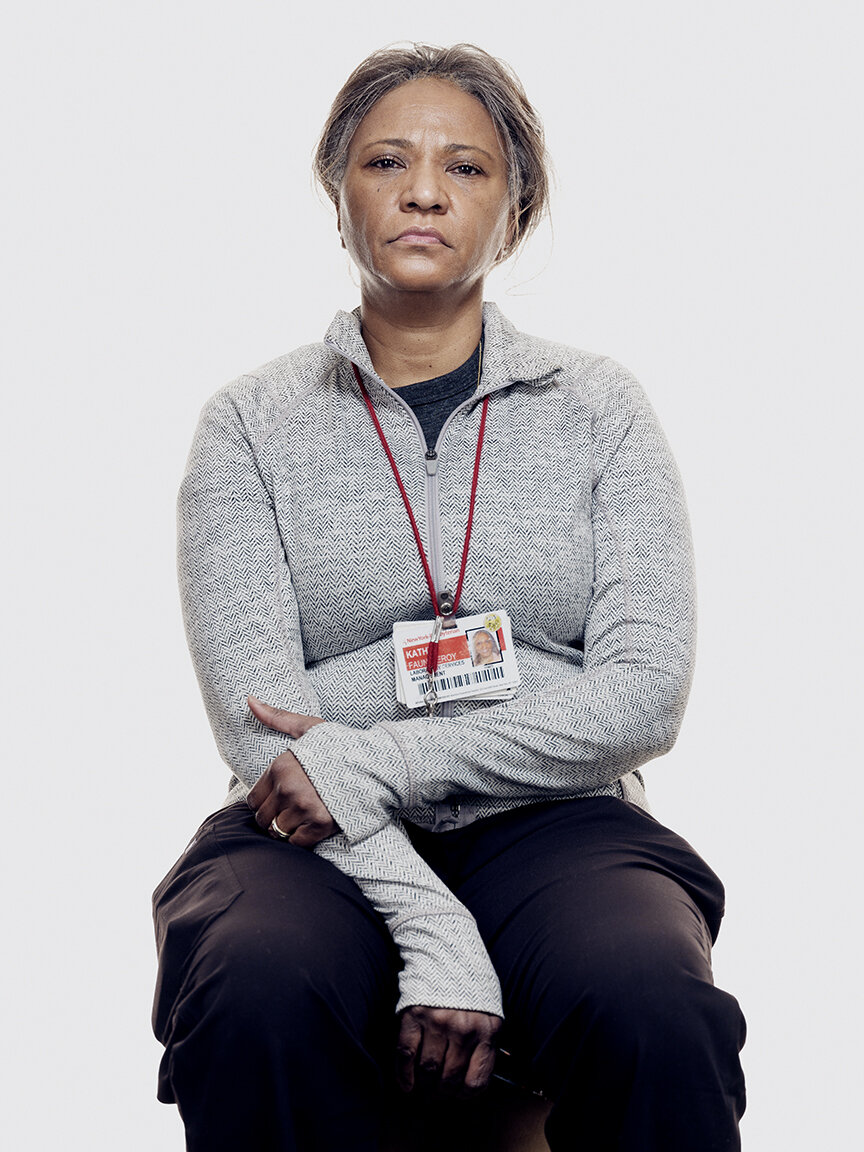

“We knew that it was coming, but we were not prepared. I was at work, and we had an emergency meeting with our manager. We stopped what we were doing, and it was announced that our unit was COVID-positive. It was very frightening. It was a feeling that I want to leave this place and I want to go home to my loved ones. But obviously you can’t because you have patients to take care of; you have five, six patients at a time.”

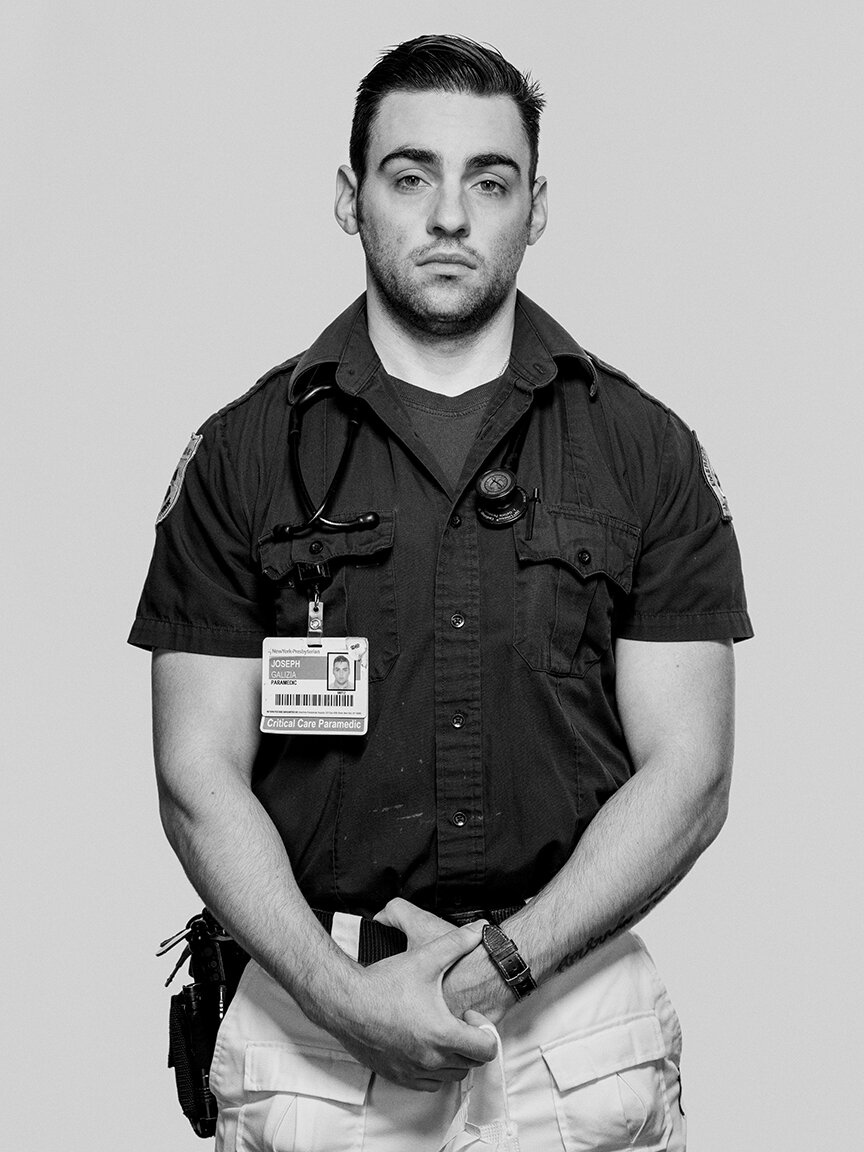

“This Covid virus is affecting a lot of different people, even people with no known medical histories or, you know, present comorbidities. But people who do have medical histories such as hypertension, diabetes, smokers - they’re really being affected by it, like, severely, some even to the point of death. So I just hope that after all this is over, people learn to take better care of themselves.”

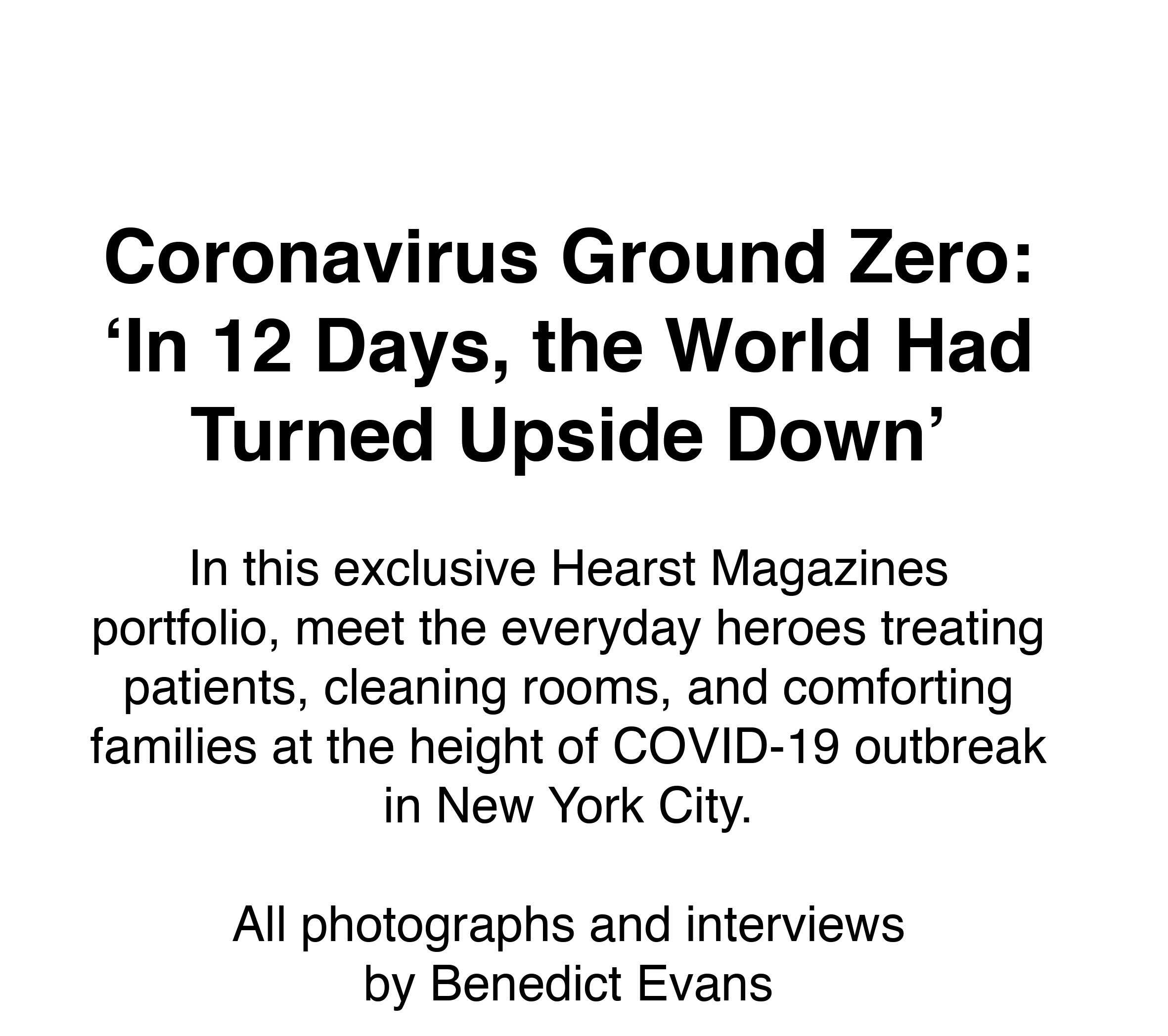

“What was on my mind yesterday when I was on my way to work was fear. It was one of the first times I’ve been back to the bedside in two and a half years. I’m in an education role now, so I was afraid that I’d lost my skill. Luckily, I didn’t, but there was fear. And there was fear of catching it. You know, I’m worried about myself. I’m worrying about bringing it home to my family. But there’s also confidence, and as soon as I walked in here, I knew I had a job to do and the patients were relying on me to care for them, and although I wasn’t in the COVID unit, I was with the other patients who are even more scared and going through surgery, and I had to be there for them. So I became confident.”

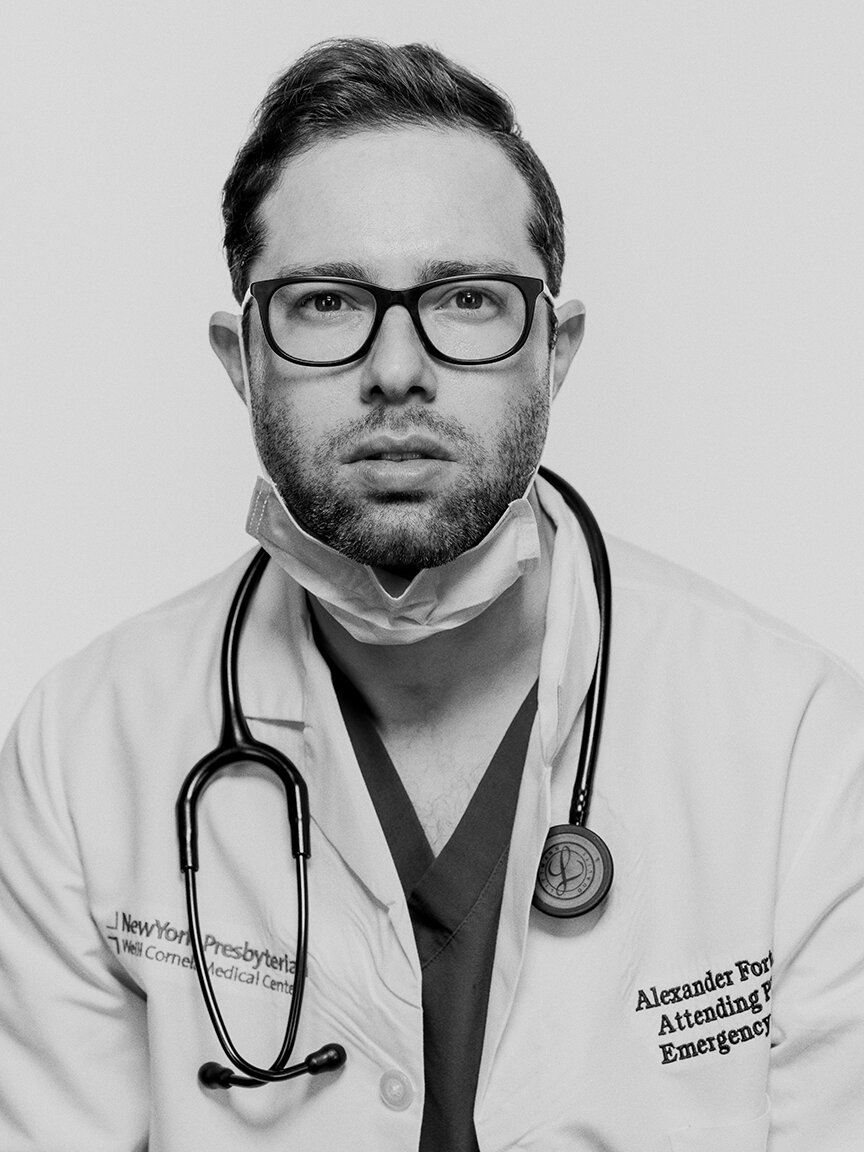

“I feel personally afraid for my own health, for - albeit it’s small - the risk that is out there. Seeing friends get sick, and seeing colleagues critically ill, I think definitely makes this entire crisis take on a whole different meaning.”

“I probably check in with my family more frequently than I used to, just a phone call or a text. That’s grounding for me. Because of my exposure, my six-year-old is staying with my in-laws. He’ll come out of the house and we maintain distance. He brings the dog and we go on these long walks. Sometimes we’re going at night because when I come home, it’s late. My son invented shadow hugs, where we stand just so that the streetlights hit us just right, we get our shadows to hug and give high-fives, and those are the best five minutes of my day.”

“I think after that first week, I became numb. And in order to do this job, you have to be able, in some ways, to separate out the suffering of the patients, the families, to do your job. I tend to be mission oriented. And the mission is: Come in, take care of patients, do everything you can to make them better.”

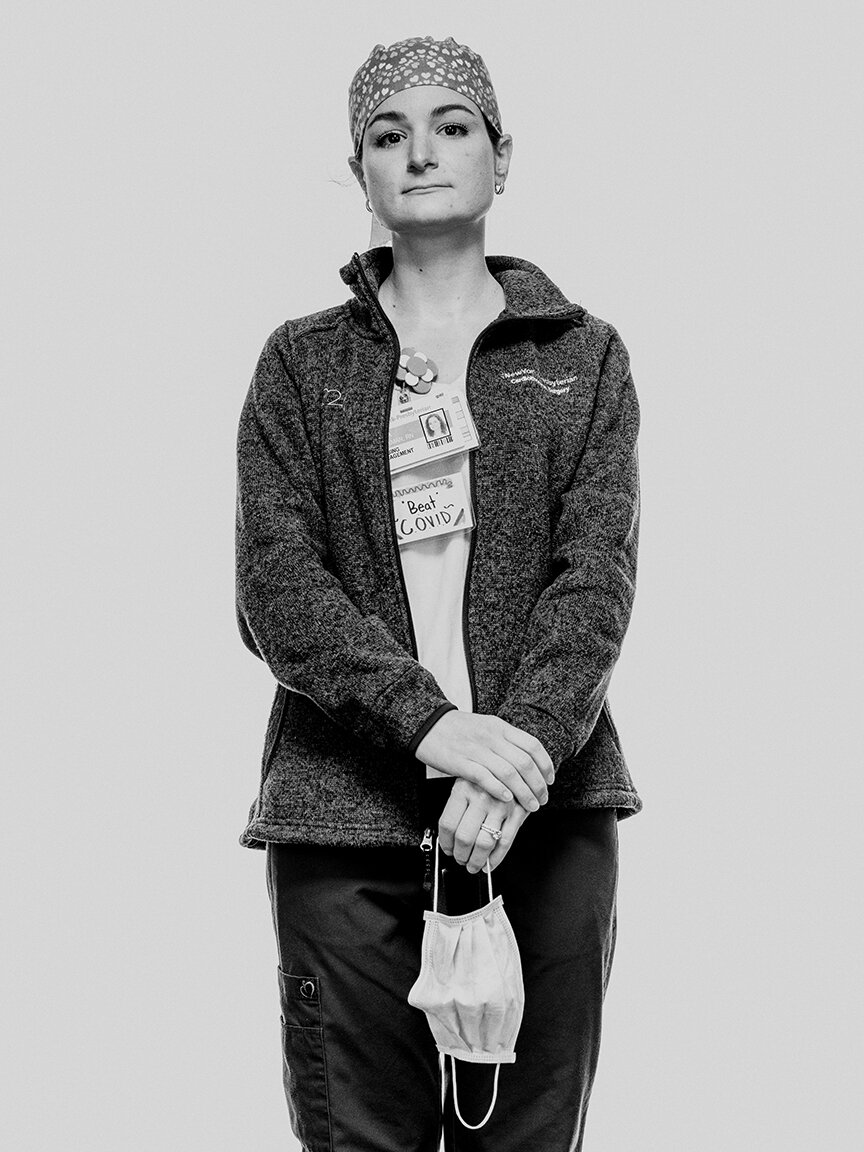

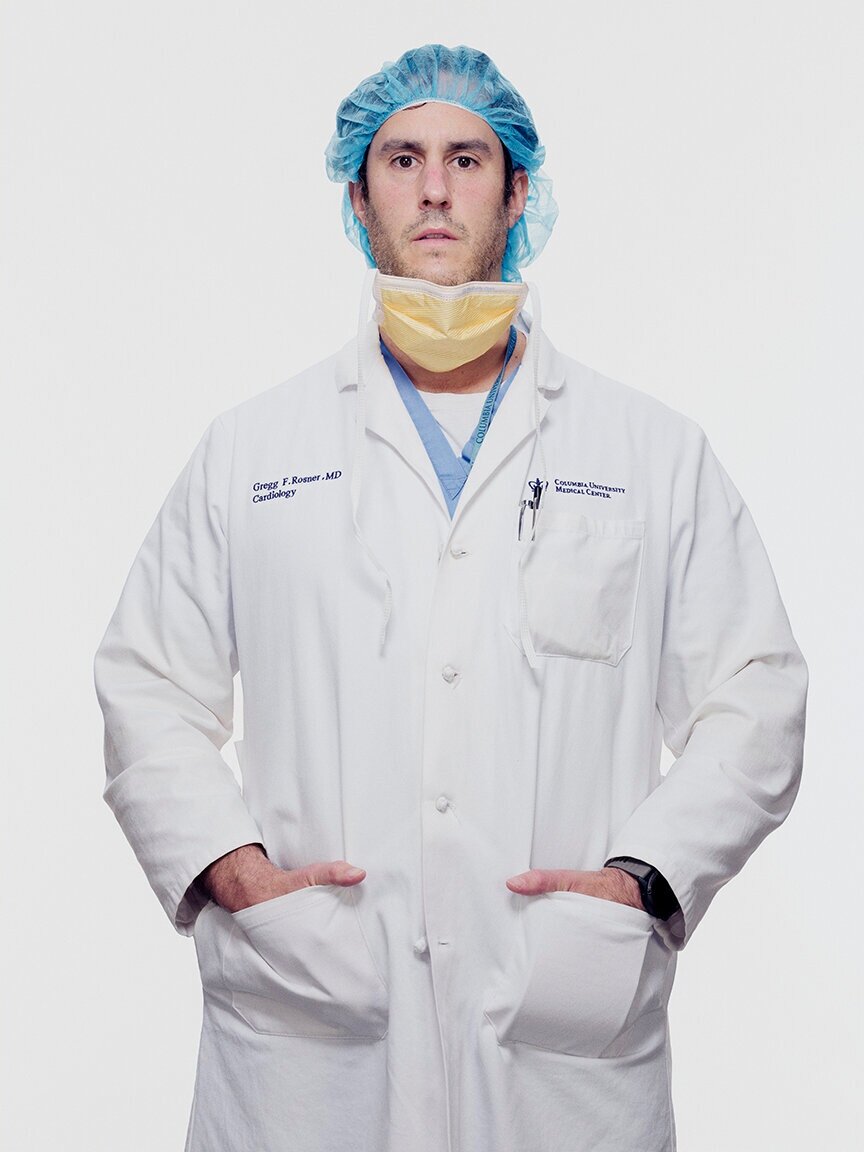

“I’m a little anxious when I’m heading in to work. You know, I think your nerves get to you when you’re not doing something. But I found that, for the most part, when I get to work—it’s a familiar place, it’s a place I’ve been for years at this point, it’s the people I know, it’s the same things that I’ve done every day before this. And so the longer I manage the shift, the more relaxed I tend to be, just because it’s familiar. But that clock kind of resets every day, too.

Work is usually pretty much nonstop. You kind of take a deep breath at the start of 12 hours and you exhale 12 hours later. Outside of work, I’m very lucky to have a family who has stayed with me in the city. So my life outside of work is where I recharge as much as possible just being with my wife and my kids. But each shift is 12 hours of pretty much nonstop.”

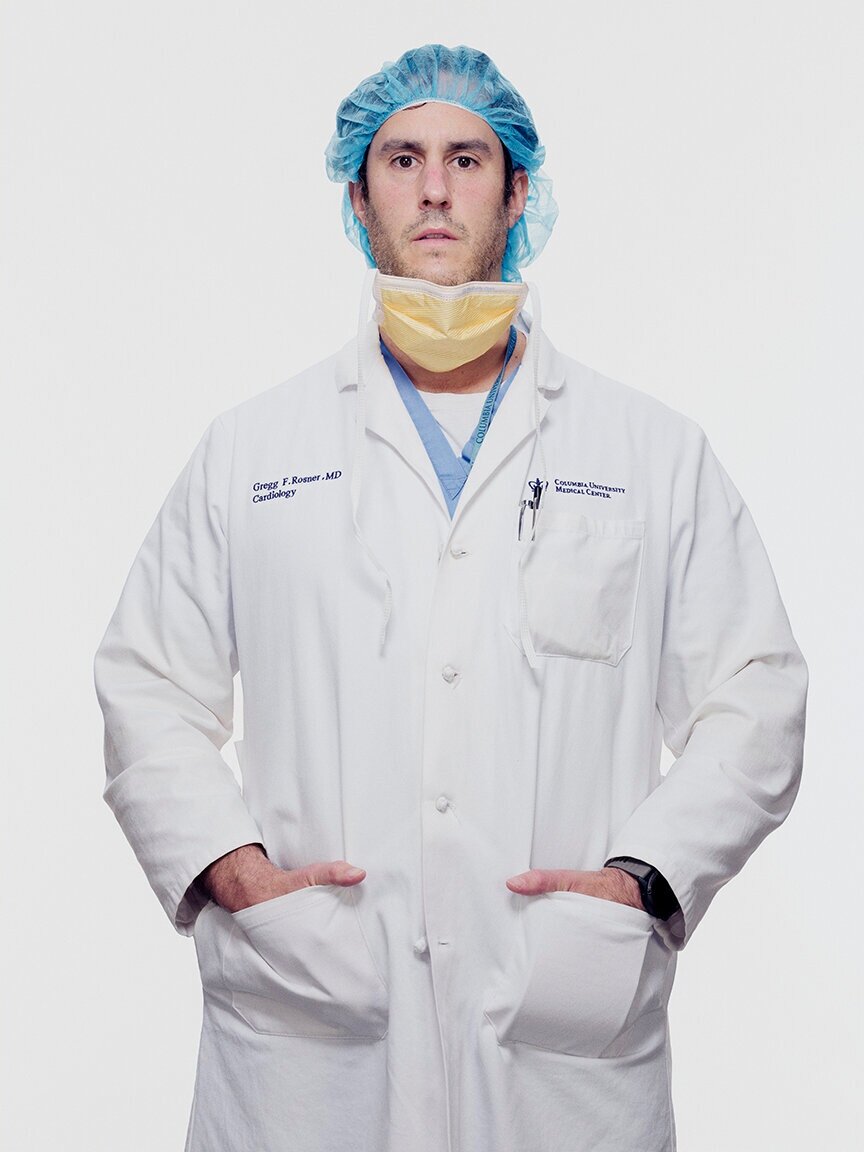

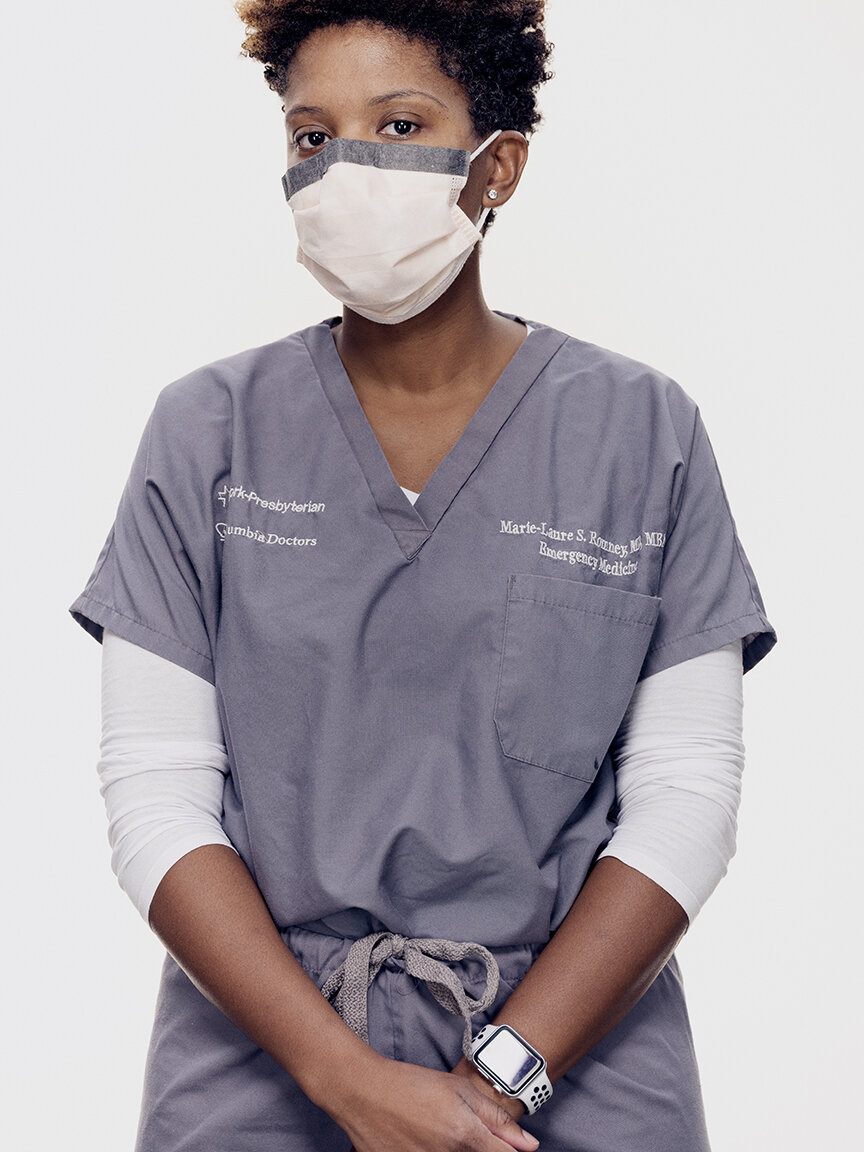

“The gravity of the situation really hit me when I went to one of our hospitals, one of the EDs (emergency departments), and it was unrecognizable. It felt like I’d walked into an intensive-care unit and not the ED that I’d been working in for the last 18 months. I think I was mostly struck by how sick all the patients were, but also by the fact that they were all by themselves without family there. It was a really challenging moment, a very somber moment.”

“Yesterday, what was on my mind is how are we going to deal with tomorrow? What are we going to do differently? How are we going to prepare? Constantly watching the news to see where the numbers are. When are we going to plateau? What are the number of deaths gonna be tomorrow versus today? That’s what’s been going on day by day: How many patients are going to require ventilators? How are we doing overall, not only in New York but throughout the country?”

“I really hope that people have a much bigger understanding of how we’re all connected- at a smaller lever, like neighbors in a community, and also on a global level. The one thing we’ve seen is how this spread rapidly from one singular area in a foreign country to the entire world in the span of weeks. How we interact with each other day-to-day can and will impact people around us.”

“My supervisor called me to the side and asked me if I had a problem going into these rooms with COVID patients. I said, ‘No, I have no problem. As long as I have the proper PPEs and the equipment, I wouldn’t mind going in.’ If that was me in that bed, I would like people to come inside and, you know, clean for me, make sure that everything is clean. Because that’s what we’re here to do: Make sure everything is clean and organize and there’s no garbage, so the doctors and the nurses can do their jobs. Make it easier for them. Of course, I’m tired and stressed, but I feel good about it, because i’m helping out. I’m contributing to this cause. I feel like the word that describes me is brave. Not just me, but also my coworkers. The few of us that are going inside these rooms - were brave.”

“I actually tested positive, and I had 12 days at home quite sick. About three days after I was isolated, my daughter started walking. And I mean, we must have been waiting for, like, three months every day for her to start walking. It was like, ‘when is she gonna let go of that last finger?’ And then then that day, she stood up and walked out of the room like she always could have. And my wife called me, and it just broke my heart. I had been so looking forward to that moment.”

“I signed up for this. This is what I love to do. This is what I’m good at. I was one of the earliest paramedics in New York City, in 1977, and I’ve been through just about every disaster in New York City: both of the New York City World Trade Center events, plane crashes, the HIV/AIDS epidemic back in the ‘80s. What gets me, what inspires me, is to come to work every day and realize we can make a difference and that my being here is important to the institution, to the patients, to our colleagues, and I’m making a difference. I do the best I can to take care of myself and make sure that I’m protected, but they know this is my job. No different from cops or firefighters or, you know, fighter pilots. This is what we’ve signed on to do. And this is what we love to do. So we’re gonna keep doing it, and it’s a privilege to be able to be here.”

“This is what I was trained to do. I’ve spent more than 30 years doing this job. And you learn in school and you learn in safety training that you have to be ready for an event like this. And you always have it in the back of your mind, but you never really think that it’s actually going to happen. But when it does, you go right to the training that you had. So I feel good that I was trained properly and that I was able to bring my best to this situation.

I have moments where I duck into a bathroom to pray. Sometimes.”

“The lowest point is having to walk these patients through saying goodbye to their family, whether that’s on the phone or through FaceTime. We don’t know what happens once we put a patient on a ventilator. Some people don’t make it, and so one of the most challenging parts of this whole disease is that we have to witness people saying goodbye to their families potentially. It’s really hard.”

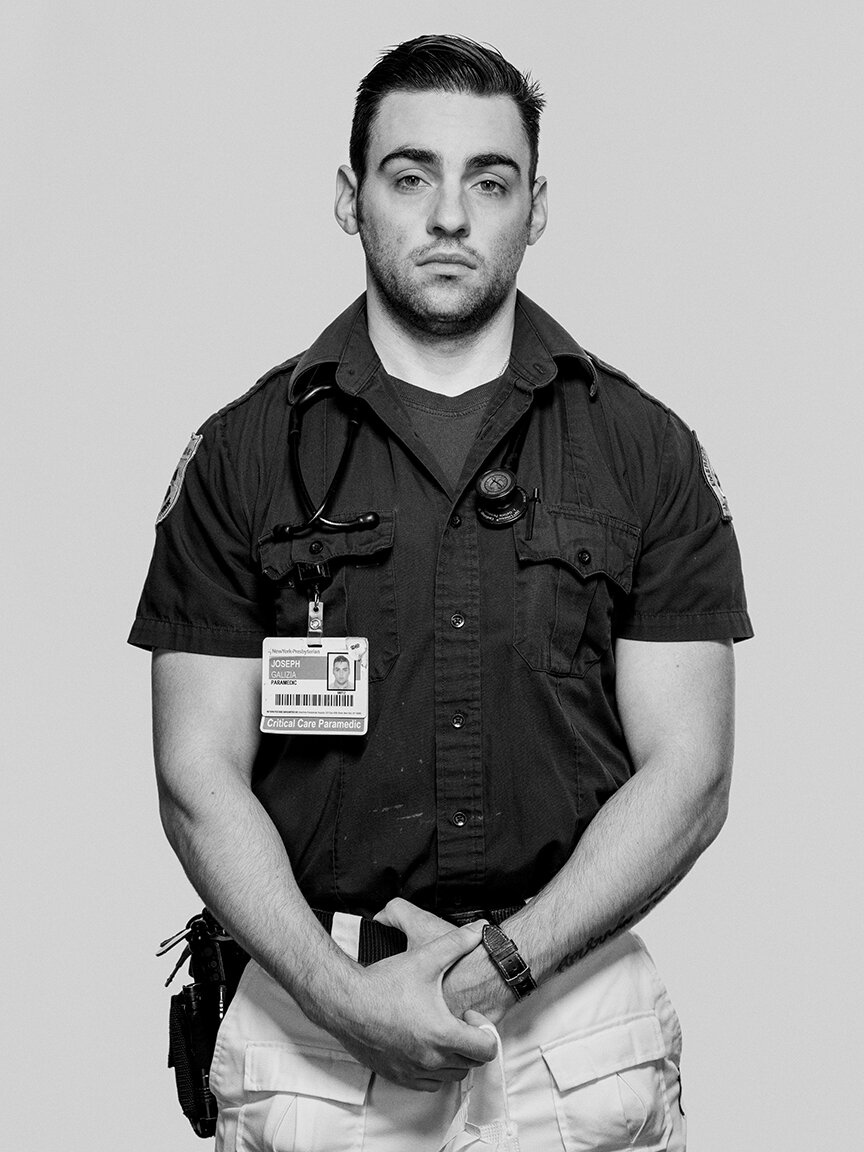

MY INSPIRATION “My mom. She was a nurse. She’s been through a lot raising the three of us - my sister, my brother, and me. Also, I’ve been in the U.S. Marine Corps, so I’ve been through wars. I’ve been deployed to Iraq. I got through that; I’m pretty sure I’m gonna get through this. Kind of looks like, ‘Hey, I’ve been through worse, and we can get through this. We’re New Yorkers, you know?”

“Yesterday and the day before and the day before and the day before- they all kind of just melt into one at this point. This is my 28th day in a row. It’s just each day you come in and it’s a new crisis. We try to deal with them as quickly and as professionally as we can. COVID-19 is not like anything we’ve ever seen. It’s very slow. These patients, they stay sick for so much longer than what we’re used to. So each day the hope is that there’s gonna be an improvement. This disease is attacking everyone’s lungs in such a bad way. And it’s so furious. And it’s relentless. And then when we actually do get somebody off a ventilator, it’s what keeps us going.”

“We knew that it was coming, but we were not prepared. I was at work, and we had an emergency meeting with our manager. We stopped what we were doing, and it was announced that our unit was COVID-positive. It was very frightening. It was a feeling that I want to leave this place and I want to go home to my loved ones. But obviously you can’t because you have patients to take care of; you have five, six patients at a time.”

“This Covid virus is affecting a lot of different people, even people with no known medical histories or, you know, present comorbidities. But people who do have medical histories such as hypertension, diabetes, smokers - they’re really being affected by it, like, severely, some even to the point of death. So I just hope that after all this is over, people learn to take better care of themselves.”

“What was on my mind yesterday when I was on my way to work was fear. It was one of the first times I’ve been back to the bedside in two and a half years. I’m in an education role now, so I was afraid that I’d lost my skill. Luckily, I didn’t, but there was fear. And there was fear of catching it. You know, I’m worried about myself. I’m worrying about bringing it home to my family. But there’s also confidence, and as soon as I walked in here, I knew I had a job to do and the patients were relying on me to care for them, and although I wasn’t in the COVID unit, I was with the other patients who are even more scared and going through surgery, and I had to be there for them. So I became confident.”

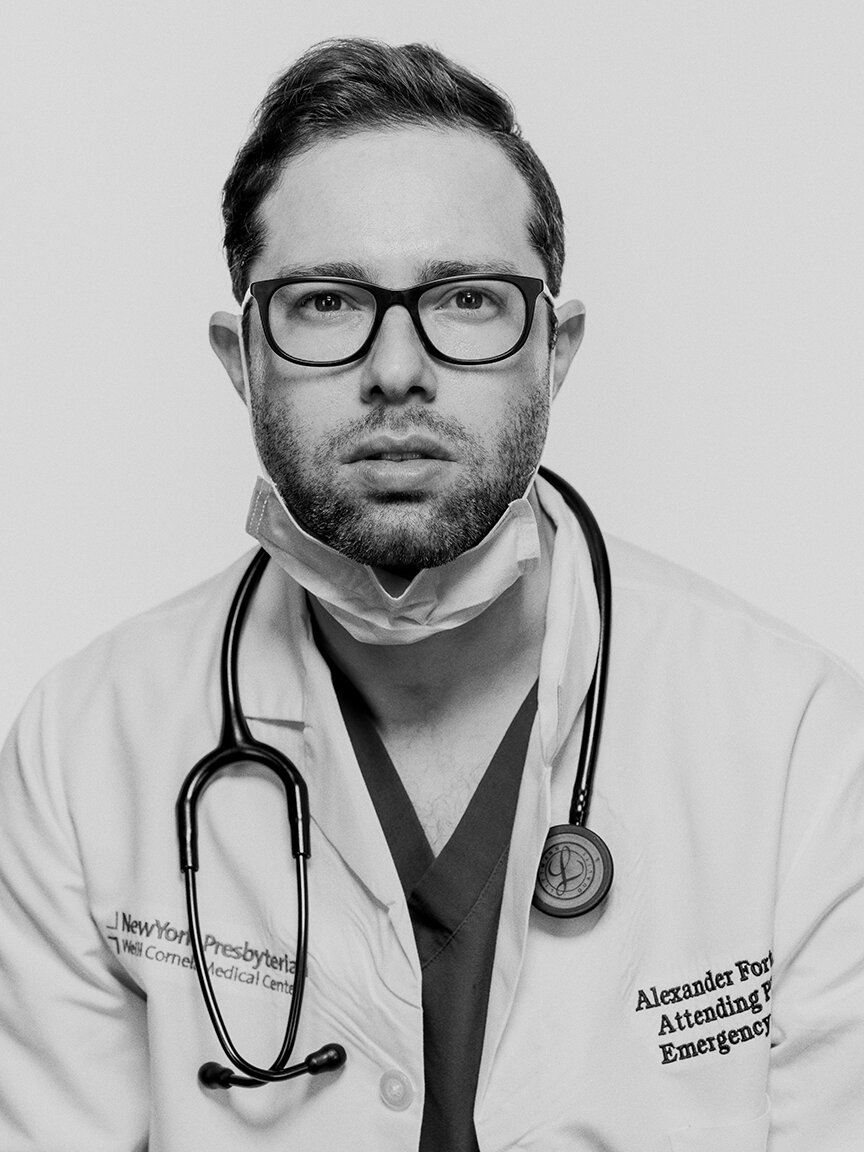

“I feel personally afraid for my own health, for - albeit it’s small - the risk that is out there. Seeing friends get sick, and seeing colleagues critically ill, I think definitely makes this entire crisis take on a whole different meaning.”

“I probably check in with my family more frequently than I used to, just a phone call or a text. That’s grounding for me. Because of my exposure, my six-year-old is staying with my in-laws. He’ll come out of the house and we maintain distance. He brings the dog and we go on these long walks. Sometimes we’re going at night because when I come home, it’s late. My son invented shadow hugs, where we stand just so that the streetlights hit us just right, we get our shadows to hug and give high-fives, and those are the best five minutes of my day.”

“I think after that first week, I became numb. And in order to do this job, you have to be able, in some ways, to separate out the suffering of the patients, the families, to do your job. I tend to be mission oriented. And the mission is: Come in, take care of patients, do everything you can to make them better.”

“I’m a little anxious when I’m heading in to work. You know, I think your nerves get to you when you’re not doing something. But I found that, for the most part, when I get to work—it’s a familiar place, it’s a place I’ve been for years at this point, it’s the people I know, it’s the same things that I’ve done every day before this. And so the longer I manage the shift, the more relaxed I tend to be, just because it’s familiar. But that clock kind of resets every day, too.

Work is usually pretty much nonstop. You kind of take a deep breath at the start of 12 hours and you exhale 12 hours later. Outside of work, I’m very lucky to have a family who has stayed with me in the city. So my life outside of work is where I recharge as much as possible just being with my wife and my kids. But each shift is 12 hours of pretty much nonstop.”

“The gravity of the situation really hit me when I went to one of our hospitals, one of the EDs (emergency departments), and it was unrecognizable. It felt like I’d walked into an intensive-care unit and not the ED that I’d been working in for the last 18 months. I think I was mostly struck by how sick all the patients were, but also by the fact that they were all by themselves without family there. It was a really challenging moment, a very somber moment.”

“Yesterday, what was on my mind is how are we going to deal with tomorrow? What are we going to do differently? How are we going to prepare? Constantly watching the news to see where the numbers are. When are we going to plateau? What are the number of deaths gonna be tomorrow versus today? That’s what’s been going on day by day: How many patients are going to require ventilators? How are we doing overall, not only in New York but throughout the country?”

“I really hope that people have a much bigger understanding of how we’re all connected- at a smaller lever, like neighbors in a community, and also on a global level. The one thing we’ve seen is how this spread rapidly from one singular area in a foreign country to the entire world in the span of weeks. How we interact with each other day-to-day can and will impact people around us.”

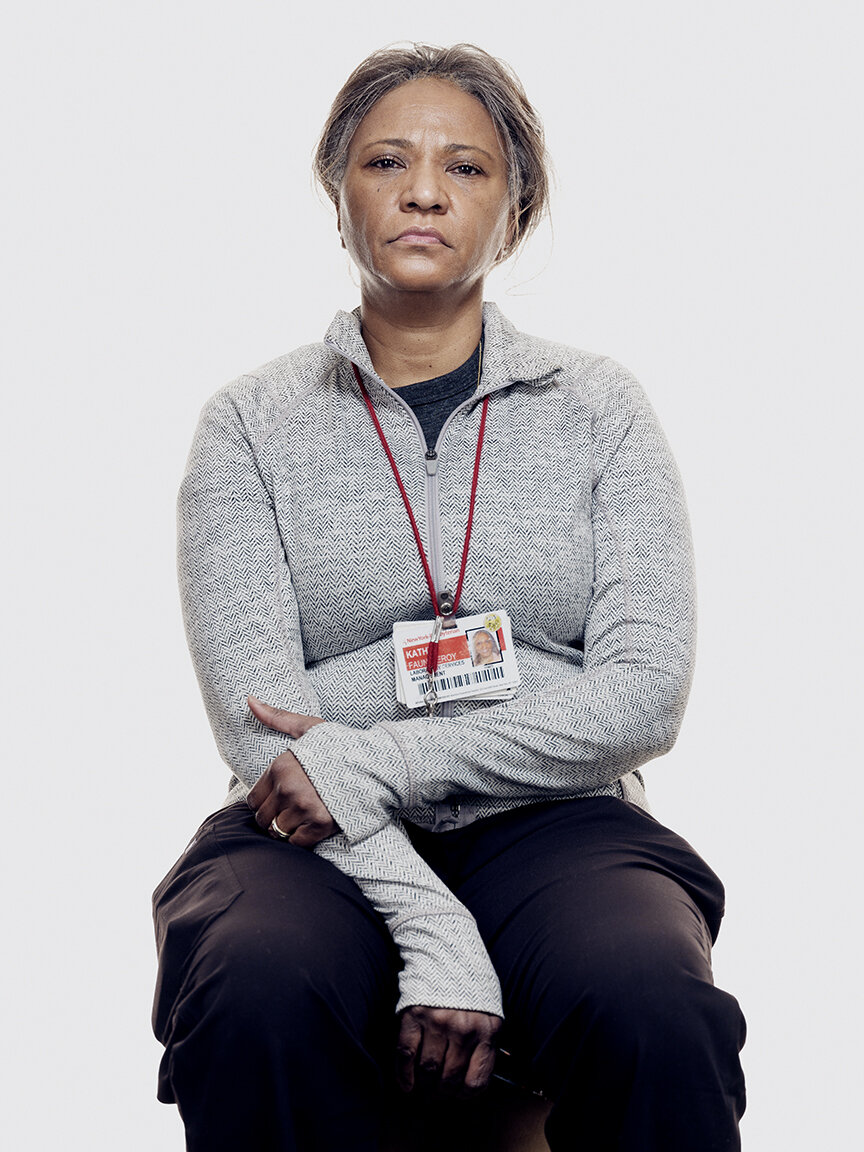

“My supervisor called me to the side and asked me if I had a problem going into these rooms with COVID patients. I said, ‘No, I have no problem. As long as I have the proper PPEs and the equipment, I wouldn’t mind going in.’ If that was me in that bed, I would like people to come inside and, you know, clean for me, make sure that everything is clean. Because that’s what we’re here to do: Make sure everything is clean and organize and there’s no garbage, so the doctors and the nurses can do their jobs. Make it easier for them. Of course, I’m tired and stressed, but I feel good about it, because i’m helping out. I’m contributing to this cause. I feel like the word that describes me is brave. Not just me, but also my coworkers. The few of us that are going inside these rooms - were brave.”

“I actually tested positive, and I had 12 days at home quite sick. About three days after I was isolated, my daughter started walking. And I mean, we must have been waiting for, like, three months every day for her to start walking. It was like, ‘when is she gonna let go of that last finger?’ And then then that day, she stood up and walked out of the room like she always could have. And my wife called me, and it just broke my heart. I had been so looking forward to that moment.”

“I signed up for this. This is what I love to do. This is what I’m good at. I was one of the earliest paramedics in New York City, in 1977, and I’ve been through just about every disaster in New York City: both of the New York City World Trade Center events, plane crashes, the HIV/AIDS epidemic back in the ‘80s. What gets me, what inspires me, is to come to work every day and realize we can make a difference and that my being here is important to the institution, to the patients, to our colleagues, and I’m making a difference. I do the best I can to take care of myself and make sure that I’m protected, but they know this is my job. No different from cops or firefighters or, you know, fighter pilots. This is what we’ve signed on to do. And this is what we love to do. So we’re gonna keep doing it, and it’s a privilege to be able to be here.”

“This is what I was trained to do. I’ve spent more than 30 years doing this job. And you learn in school and you learn in safety training that you have to be ready for an event like this. And you always have it in the back of your mind, but you never really think that it’s actually going to happen. But when it does, you go right to the training that you had. So I feel good that I was trained properly and that I was able to bring my best to this situation.

I have moments where I duck into a bathroom to pray. Sometimes.”

“The lowest point is having to walk these patients through saying goodbye to their family, whether that’s on the phone or through FaceTime. We don’t know what happens once we put a patient on a ventilator. Some people don’t make it, and so one of the most challenging parts of this whole disease is that we have to witness people saying goodbye to their families potentially. It’s really hard.”

MY INSPIRATION “My mom. She was a nurse. She’s been through a lot raising the three of us - my sister, my brother, and me. Also, I’ve been in the U.S. Marine Corps, so I’ve been through wars. I’ve been deployed to Iraq. I got through that; I’m pretty sure I’m gonna get through this. Kind of looks like, ‘Hey, I’ve been through worse, and we can get through this. We’re New Yorkers, you know?”

“Yesterday and the day before and the day before and the day before- they all kind of just melt into one at this point. This is my 28th day in a row. It’s just each day you come in and it’s a new crisis. We try to deal with them as quickly and as professionally as we can. COVID-19 is not like anything we’ve ever seen. It’s very slow. These patients, they stay sick for so much longer than what we’re used to. So each day the hope is that there’s gonna be an improvement. This disease is attacking everyone’s lungs in such a bad way. And it’s so furious. And it’s relentless. And then when we actually do get somebody off a ventilator, it’s what keeps us going.”